How to use systemd for system administration on Debian

Last updated on October 1, 2020 by Gabriel Cánepa

Soon enough, hardly any Linux user will be able to escape the ever growing grasp that systemd imposes on Linux, unless they manually opt out. systemd has created more technical, emotional, and social issues than any other piece of software as of late. This predominantly came to show in the heated discussions also dubbed as the Init Wars, that occupied parts of the Debian developer body for months. While the Debian Technical Comittee finally decided to include systemd in Debian 8 Jessie, there were efforts to supersede the decision by a General Resolution, and even threats to the health of developers in favor of systemd.

This goes to show how deep systemd interferes with the way of handling Linux systems that has, in large parts, been passed down to us from the Unix days. Theorems like "one tool for the job" are overthrown by the new kid in town. Besides substituting sysvinit as init system, it digs deep into system administration. For right now a lot of the commands you are used to will keep on working due to the compatibility layer provided by the package systemd-sysv. That might change as soon as systemd 214 is uploaded to Debian, destined to be released in the stable branch with Debian 8 Jessie. From thereon, users need to utilize the new commands that come with systemd for managing services, processes, switching run levels, and querying the logging system. A workaround is to set up aliases in .bashrc.

So let's have a look at how systemd will change your habits of administrating your computers and the pros and cons involved. Before making the switch to systemd, it is a good security measure to save the old sysvinit to be able to still boot, should systemd fail. This will only work as long as systemd-sysv is not yet installed, and can be easily obtained by running:

# cp -av /sbin/init /sbin/init.sysvinit

Thusly prepared, in case of emergency, just append:

init=/sbin/init.sysvinit

to the kernel boot-time parameters.

Basic Usage of systemctl

systemctl is the command that substitutes the old /etc/init.d/foo start/stop, but also does a lot more, as you can learn from its man page.

Some basic use-cases are:

systemctl- list all loaded units and their state (where unit is the term for a job/service)systemctl list-units- list all unitssystemctl start [NAME...]- start (activate) one or more unitssystemctl stop [NAME...]- stop (deactivate) one or more unitssystemctl disable [NAME...]- disable one or more unit filessystemctl list-unit-files- show all installed unit files and their statesystemctl --failed- show which units failed during bootsystemctl --type=mount- filter for types; types could be: service, mount, device, socket, targetsystemctl enable debug-shell.service- start a root shell on TTY 9 for debugging

For more convinience in handling units, there is the package systemd-ui, which is started as user with the command systemadm.

Switching runlevels, reboot and shutdown are also handled by systemctl:

systemctl isolate graphical.target- take you to what you know as init 5, where your X-server runssystemctl isolate multi-user.target- take you to what you know as init 3, TTY, no Xsystemctl reboot- shut down and reboot the systemsystemctl poweroff- shut down the system

All these commands, other than the ones for switching runlevels, can be executed as normal user.

Basic Usage of journalctl

systemd does not only boot machines faster than the old init system, it also starts logging much earlier, including messages from the kernel initialization phase, the initial RAM disk, the early boot logic, and the main system runtime. So the days where you needed to use a camera to provide the output of a kernel panic or otherwise stalled system for debugging are mostly over.

With systemd, logs are aggregated in the journal which resides in /var/log/. To be able to make full use of the journal, we first need to set it up, as Debian does not do that for you yet:

# addgroup --system systemd-journal # mkdir -p /var/log/journal # chown root:systemd-journal /var/log/journal # gpasswd -a $user systemd-journal

That will set up the journal in a way where you can query it as normal user. Querying the journal with journalctl offers some advantages over the way syslog works:

journalctl --all- show the full journal of the system and all its usersjournalctl -f- show a live view of the journal (equivalent to "tail -f /var/log/messages")journalctl -b- show the log since the last bootjournalctl -k -b -1- show all kernel logs from the boot before last (-b -1)journalctl -b -p err- shows the log of the last boot, limited to the priority "ERROR"journalctl --since=yesterday- since Linux people normally do not often reboot, this limits the size more than -b wouldjournalctl -u cron.service --since='2014-07-06 07:00' --until='2014-07-06 08:23'- show the log forcronfor a defined timeframejournalctl -p 2 --since=today- show the log for priority 2, which covers emerg, alert and crit; resemblessyslogpriorities emerg (0), alert (1), crit (2), err (3), warning (4), notice (5), info (6), debug (7)journalctl > yourlog.log- copy the binary journal as text into your current directory

Journal and syslog can work side-by-side. On the other hand, you can remove any syslog packages like rsyslog or syslog-ng once you are satisfied with the way the journal works.

For very detailed output, append systemd.log_level=debug to the kernel boot-time parameter list, and then run:

# journalctl -alb

Log levels can also be edited in /etc/systemd/system.conf.

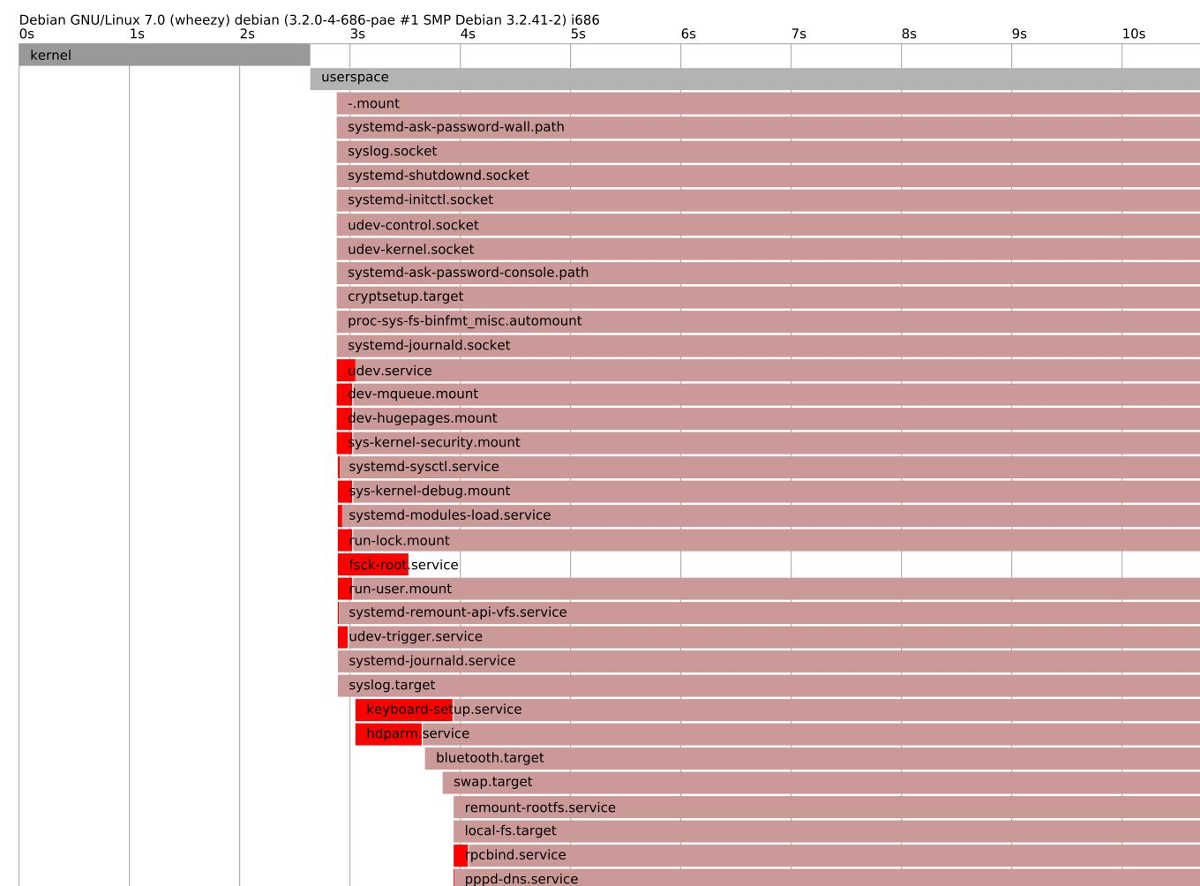

Analyzing the Boot Process with systemd

systemd allows you to effectively analyze and optimize your boot process:

systemd-analyze- show how long the last boot took for kernel and userspacesystemd-analyze blame- show details of how long each service took to startsystemd-analyze critical-chain- print a tree of the time-critical chain of unitssystemd-analyze dot | dot -Tsvg > systemd.svg- put a vector graphic of your boot process (requiresgraphvizpackage)systemd-analyze plot > bootplot.svg- generate a graphical timechart of the boot process

systemd has pretty good documentation for such a young project under heavy developement. First of all, there is the 0pointer series by Lennart Poettering. The series is highly technical and quite verbose, and holds a wealth of information. Another good source is the distro agnostic Freedesktop info page with the largest collection of links to systemd resources, distro specific pages, bugtrackers and documentation. A quick glance at:

# man systemd.index

will give you an overview of all systemd man pages. The command structure for systemd for various distributions is pretty much the same, differences are found mainly in the packaging.

Support Xmodulo

This website is made possible by minimal ads and your gracious donation via PayPal or credit card

Please note that this article is published by Xmodulo.com under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. If you would like to use the whole or any part of this article, you need to cite this web page at Xmodulo.com as the original source.

Xmodulo © 2021 ‒ About ‒ Write for Us ‒ Feed ‒ Powered by DigitalOcean